2/28/2019

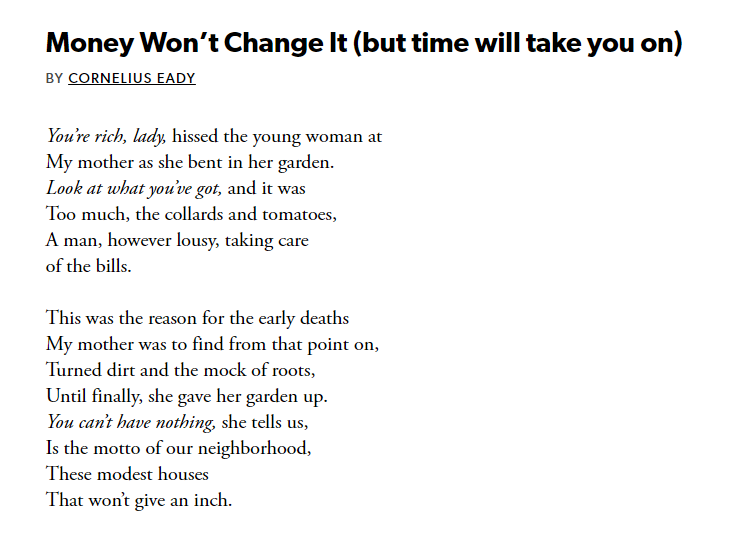

“Money Won’t Change It (but time will take you on)” by Cornelius Eady

The first two lines start the poem off and lead it in an interesting direction. “You’re rich, lady, hissed the young woman” is immediately contrasted by “at / My mother as she bent in her garden.” Generally, someone toiling in a garden would not come across as rich, and so the topic is hinted at here without revealing its intent, and this hint could be describing the “it” (referred to in the title) that money can’t change. Next, the speaker notes that “it was / Too much, the collards and tomatoes”, perhaps indicating that the mother feels lesser about her modest belongings after seeing the young woman, who has even less. Another point adding to their richness in the girl’s eyes is the lousy man taking care of the bills. These things seem commonplace and even menial to some, but to those who struggle, particularly those from lower-income neighborhoods as is the poet, these are luxuries that are only dreamed of. This analysis leads into the second stanza, which details the resulting feelings that the mother experiences after this encounter. The speaker tells that “from that point on”, his mother experienced “early deaths”, “Until finally, she gave her garden up.” It is shown that the enthusiasm and effort put into her garden originally has been diminished. The author manages to clearly indicate emotion, and the specific emotions impressed upon the mother in the first stanza, are then transferred to the speaker and his siblings in the second. The way I interpret the last four lines is that the mother tries her best to make something out of the very little that they have, but that something is always there to hold them back, and that based on her experience they will never be able to get far. I think it is also interesting to note that this poem is 14 lines, similar to traditional sonnets by earlier poets, yet told in free verse. Other than that, it lacks the other qualities indicative of this poem format, but the line number paired with the decisive final couplet is an interesting way to relate the author’s poetry to that of his predecessors, while describing conflicts entirely new to his own generation.